~ Roman Monographs ~ Fountains · part I · Ancient Fountains PAGE 1 |

|---|

FOREWORD

| The monograph Fountains comes as a natural sequel to the previous one about the aqueducts. Actually, this was supposed to be one of the very first sections written for the website. But a comprehensive description of such an extensive topic clashed with the limited amount of disk space and traffic provided by the company that originally hosted Virtual Roma free of charge. For this reason the project took years to be published. And although now it is here, there is a good chance that in time further pages may be added. To compile a full picture catalogue of all the fountains extant in Rome, from the tiniest ones to the largest, would have been a stimulating challenge, but I prefer to describe 'only' the ones worthy of being mentioned. |

For this reason a few minor fountains have been intentionally disregarded.

Also courtyard fountains, typically found in palaces and mansions once belonging to noble families, have been left out, as very often they are not accessible to the general public.

courtyard fountain (1669) in via della Panetteria 15 |

Some of them are works of little or no interest at all; some others, instead, are creations by renowned artists (such as the one shown on the left, for which Gianlorenzo Bernini is credited). But since they are private properties, regardless of their artistic value, they cannot be fully considered as 'fountains of Rome'. Furthermore, since a policy of this website is not to deal with the Vatican, the few fountains officially located within the boundaries of the tiny country have not been taken into consideration (with the only exception of the two twin ones found in St.Peter's Square): strictly speaking, they are not in Rome (nor in Italy, either!), but most of all they are not freely reachable and enjoyable as the Roman ones, described in these pages. |

courtyard fountain (late 1600s) in via della Scrofa 70 |

|---|

Despite the cuts, this is still a 26 page monograph (the largest of this website, so far!), in which about 200 fountains are extensively commented and illustrated with over 500 photographs and drawings.

By moving the mouse cursor over the pictures, the exact location of each fountain appears. The loading of some pages may be slower than others, according to the number of illustrations they contain.

This monograph consists of the following parts (clickable index):

...even this may happen in Rome's fountains! →

|

|---|

ANCIENT FOUNTAINS

THE ORIGINS

| Rome's earliest inhabitants, i.e. a number of tribes scattered over the mythical

Seven Hills, drew water directly from the Tiber. They could also use small pits or wells for storing rain water, such as the one shown on the right, found by the area of Forum of Caesar, which dates back as far as the 6th century BC. During the Republican age, the Romans exploited the few underground springs extant in the inhabited areas to build the first fountains. Many of their names, such as Fons Lupercalis, Fons Apollinaris, Fons Pici, Fons Mercurii, and others, are mentioned by literary sources, and in some cases we also know approximately where they were located. |

small well (6th century BC) |

|---|

Some of them were certainly huge, such as the Piscina Publica, i.e. the "public pool" in the southern part of the city, which might have acted as a reservoir rather than as a fountain. By the early imperial age (1st century AD) it had already disappeared, but emperor Octavianus Augustus gave its name to the city's 12th district, so its memory lingered for quite a long time among the local inhabitants.

the site of the Lacus Iuturnae (courtesy of Kalervo Koskimies) |

Today very little is left of the fountains of the Republican age, and the few remains still visible barely remind us of their original shape. Only the legends they gave birth to have been handed down in full. This is the case of the Lacus Iuturnae, named after goddess Iuturna, patron of workers whose job had a relation with water. The fountain stood in the Roman Forum's area, by the temple sacred to the Dioscuri (Castor and Pollux, the sons of Jupiter and Leda) because, according to tradition, in 499 BC, after having fought on Rome's side in a battle against the Latin League, they stopped here to drink their horses. |

|---|

Not much is left of the Lacus Curtius either, a water spring or, according to others, a simple basin for collecting rain water, located in the Forum's area, as well.

| The spot where it stands was the last part of a marsh that once stretched over the whole area where the Forum was built. But according to tradition, the spring originated when a thunderbolt cracked the ground, in 445 BC, and consul Gaius Curtius had the area surrounded with a fence. This was a religious practice: the fall of a thunderbolt was considered to presage negative events, therefore in such cases a body of ten religious ministers called bidentales presided the enclosure of the spot, and the burial of a stone as a symbolic representation of the thunderbolt. The sacrifice of a sheep then followed; on this occasion, the animal was called a bidental, and the spot too was named after it. | the site of the Lacus Curtius (courtesy of René Seindal) |

|---|

Lacus Curtius: the original relief |

A more adventurous legend tells about the Lacus Curtius as the site of a bottomless hole which - the oracle foresaw - could have been closed only by throwing in it what in Rome was most valuable; so in 362 BC the young cavalier Marcus Curtius, fully armoured and on horseback, threw himself into the hole, which

turned into a harmless spring. The relief that marks the spot illustrates this version of the story. A third version is about the chief of the Sabines, Metius Curtius, who fell into the hole. |

|---|

However, the site now appears only as an irregularly paved quadrangle, marked by the replica of a relief featuring Marcus Curtius on horseback (the original, of Republican age, is kept in the nearby Capitoline Museums).

During the Republican age the number of fountains was still insufficient for covering the population's needs, especially for those who dwelt off the area of the Forum, and many romans kept drawing water from the Tiber.

| For this reason it was not allowed to build houses within a certain distance from the river's eastern bank (the western side was mainly inhabited by immigrants and foreign merchants), and the area to be kept free from private properties was marked with stones, a number of which has been found (see picture on the right). The real wealth of water began with the making of the many aqueducts, between the 1st century BC and the 3rd century AD (see Aqueducts part I), a period during which the number of fountains in Rome considerably increased; they no longer drew water from nearby natural springs, but from the main ducts and their numerous secondary branches. public area delimitation stone → |

The Meta Sudans suffered important damages during the Middle Ages, as it already appears as a ruin in early views of the Colosseum. In 1936, due to its worsened conditions and totraffic reasons, it was definitively removed, and a round commemorative plaque was set in the center of the the spot.

|

(↑ top left) the Meta Sudans in an etching of the late 1500s and (top right) in a photograph of the early 1900s; (← left) the present condition of the site |

Emperor Domitian (AD 81-96) had this complex built close enough to the large amphiteatre so that it could be reached from the barracks by means of an underground passage. In the large courtyard of the Ludus Magnus was a small amphiteatre, for recreating the setting of the Colosseum's arena, and four triangular fountains in the corners, only one of which is now visible (map below). Today the lower half of the Ludus Magnus is buried below private buildings, and via San Giovanni in Laterano runs across its centre.

|

|

|---|

fountain in the shape of a horn, 1st century (Capitoline Museums) |

As the public fountains became more and more numerous, even larger was the number of private ones, although the latter are not the main topic of this monograph. They decorated the lavish villas of the high class, and had the most fancy shapes.

|

|---|

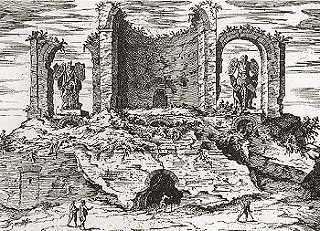

An example are the imposing ruins of the nymphaeum of Alexander Severus, located in the gardens of piazza Vittorio Emanuele, popularly known as 'Mario's Trophies'.

In the 1500s, the two groups of trophies were still standing on the ruins of the fountain (central picture below), but by the end of the century they were moved to Capitolium Square, where they are still now. They are popularly called 'Mario's Trophies', as they were believed to celebrate the victories of general Gaius Marius over the Cimbri and the Teutons (Germanic populations, in 101 BC). In recent times, though, the dating of the two sculptures has been postponed by almost two centuries, being in fact referred to emperor Domitian's victories over the Chatti (another Germanic tribe, in AD 83), or the Dacians (tribes who dwelt present Romania, in AD 89). However, they are still over one century older than the nymphaeum, so the groups were not carved for the occasion, but were clearly taken from some other pre-existing monument.

The ruins of the fountain maintained the name 'Mario's Trophies' also after the removal of the two groups. Today they act as a shelter for one of Rome's several colonies of stray cats.

the two groups removed from the nymphaeum of Alexander Severus, and (centre) a 16th century engraving that features them still in place

For the sake of completeness, we should include among the ancient fountains also the grey granite cup that faces the Basilica of Maxentius, known as Fountain of the Great Niche (not to be confused with the one by the Pincio Hill that bears the same name, described in part III), although it comes from Portus, presently Ostia, where it was found in 1696.

the remains known as 'Mario's Trophies' |

The fountain was the outlet of a secondary branch given off by the Aqua Iulia aqueduct (the latter followed the nearby eastern walls of the city, and is described in the Aqueducts monograph). A large central niche was occupied by a sculpture; further above, on the attic, rested a four horse chariot. Two marble groups featuring weapons and armour taken from barbaric populations as a trophy of war were set under an arch on both sides. The base of the monument was quadrangular, with a series of niches all around, in which other statues stood; the latter was surrounded by a large basin, where the water gushing from several outlets on the sides was collected. Unfortunately, none of the monument's original decorations is still in place, and what was its shape is only known thanks to some coins of the same age, on which the fountain was featured. |

|---|

In the 1500s, the two groups of trophies were still standing on the ruins of the fountain (central picture below), but by the end of the century they were moved to Capitolium Square, where they are still now. They are popularly called 'Mario's Trophies', as they were believed to celebrate the victories of general Gaius Marius over the Cimbri and the Teutons (Germanic populations, in 101 BC). In recent times, though, the dating of the two sculptures has been postponed by almost two centuries, being in fact referred to emperor Domitian's victories over the Chatti (another Germanic tribe, in AD 83), or the Dacians (tribes who dwelt present Romania, in AD 89). However, they are still over one century older than the nymphaeum, so the groups were not carved for the occasion, but were clearly taken from some other pre-existing monument.

The ruins of the fountain maintained the name 'Mario's Trophies' also after the removal of the two groups. Today they act as a shelter for one of Rome's several colonies of stray cats.

the two groups removed from the nymphaeum of Alexander Severus, and (centre) a 16th century engraving that features them still in place

| Nearby stands the nymphaeum of the Licinii, built around the 4th century AD. What are now remains originally formed a round dome-shaped hall, whose walls were very likely covered with paintings and precious marbles, while in the centre the water gushed from one or more statues, surrounded by flowers and plants. It stood in the gardens of the Licinii family's villa, which stretched over a wide area, now crossed by the railway lines. It is still known with its popular name, 'Temple of Medical Minerva', after a statue of the goddess unearthed nearby, which probably decorated the aforesaid gardens, and misled the finders about the real purpose of the hall. The nymphaeum is also mentioned in the tour of Aurelian's Walls, with other pictures of these impressive yet rather neglected remains. |

the remains known as 'Temple of Medical Minerva' |

|---|

| The statues that decorated ancient Roman fountains were often allegories of seas or rivers, usually portrayed as bearded figures, in reclining position, if carved in full. One of them, popularly known as Marforio (picture below), is found in the courtyard of Palazzo Nuovo, a section of the Capitoline Museums. For centuries the statue had lain in the northern part of the nearby Roman Forum area, where some maps and drawings prior to its repositioning feature it, among other scattered remains. In 1588 Sixtus V had it moved to the Capitolium Hill, likely with the purpose of turning it into a fountain again. A document of the same year states that the statue bore the inscription MARE IN FORO ("sea in the Forum"), whence the old theory according to which it may represent a sea divinity, although scholars now believe it refers to a river, likely the Tiber. The inscription is no longer readable, but the statue's nickname clearly sprang from it. ← huge head of Ocean that decorated a 2nd century fountain (Vatican Museums) |

| The old interpretation explains why its missing right arm was restored by giving it a new one that holds a sea shell. According to another version, some medieval sources mention that by the fountain once stood a temple in the Forum of Mars, and the site used to be named Marfori or Marfoli. Over the past centuries, Marforio was rather popular among the people of Rome, as it belongs to the group of so-called 'talking statues' (see the Curious and Unusual section). |

Marforio may have been part of an ancient Roman fountain |

|---|

Marforio in its original location (arrow) in a 16th century drawing of the Forum |

When Marforio was moved to the Capitolium, also its huge round basin was found. The latter, though, was left in the Forum's area, where it was turned into a drinking-trough for cattle and horses, and given a new water outlet in the shape of a grotesque face carved by Giacomo Della Porta, outstanding fountain-maker of the late 16th century. In 1816, having the basin been partly filled again with rubble, Pius VII had it moved to a more noble location, namely below the statues of the Dioscuri in front of the Quirinal Palace, while the grotesque face was reused for a small fountain by the river bank (the former is described in part III, the latter in part II). |

|---|

For the sake of completeness, we should include among the ancient fountains also the grey granite cup that faces the Basilica of Maxentius, known as Fountain of the Great Niche (not to be confused with the one by the Pincio Hill that bears the same name, described in part III), although it comes from Portus, presently Ostia, where it was found in 1696.

Fontana del Nicchione |

|

|---|

| In a similar way, when during excavation works by the foundations of Palazzo Madama (i.e. the seat of the High Chamber) a huge basin made of Egyptian granite was found, very likely a fountain once belonging to the nearby Baths of Nero (no longer standing), it was set on the same spot, in via dei Staderari, providing it with a simple modern base and a ground octagonal basin, therefore using it once again as a fountain. To be moved, disassembled, rebuilt, and then moved again, is a fate shared also by many other less ancient fountains, described in the pages of this monograph. the Roman basin in via degli Staderari → |

| PART I · page 2 THE MIDDLE AGES |

PART II SMALL FOUNTAINS |

PART III MAIN FOUNTAINS |

|---|