, the role played by Rome goes well beyond that of a simple background or a passive setting. The city interacts with the plot, with the personages, as in the passage where Tolla gets lost in the crowd caused by the castle's fireworks display, or in the passage where the Jewish

is placed under siege. Although the houses of Meo, Nuccia, Calfurnia, Marco Pepe, etc. only existed in the author's imagination, several real sites where action takes place are specifically involved; Berneri does not only mention them, he describes them, almost as if they too were taking part to the story.

The aim of this page is to briefly review these sites (also described in other sections of the website), and to compare their present look with the one they had in the 17th century, which in some cases was quite different.

the Roman Forum, as it appears today |

What Berneri describes as an uninhabited place, away from the bustling streets, where the braves used to challenge themselves with terrible stone-fights, was the present archaeological site of the Roman Forum.

The evolution of this area, from early pre-Roman times to nowadays, gives reason for its different look in time.

At first, a simple valley, where the people who lived on the top of the surrounding hills gathered every eight days to sell and buy goods, away (foras in Latin) from the territories of their respective tribes. Then the elegant downtown of the republican and imperial city, where the main temples stood; then an abandoned area during the Middle Ages, where sheep grazed, and then, as of the 15th century, the site of the cattle-market (whence the name Campo Vaccino i.e. "Cattle Field"); finally, but only since the mid 1800s, the largest and most renowned among Rome's archaeological sites, to which the old name 'Forum' was given back. |

Due to the original importance of this spot, it could have not been located elsewhere but in a crucial position, enclosed by the Capitolium Hill, where the main temples stood, the Palatine Hill, where the emperors built their palaces, and the Esquiline Hill, by whose base stretched the ill-famed Suburra district.

Since the beginning of the Middle Ages (5th-6th centuries), this area appeared more and more neglected; after Rome's christianization, pagan temples were gradually abandoned and taken down, to be recycled as building material.

Valuable marbles were taken from the Forum, some to be burned in simple furnaces and turned into mortar, others to be used for the making of churches and houses. Many statues featuring pagan emperors or gods of the old religion were destroyed. This was a die-hard attitude, which lasted over one thousand years: still in the early 18th century the remains of ancient mouments were being pillaged for the making of other works, such as the large fountain on the Janiculum Hill, built with material taken mainly from the Forum of Nerva (opposite rhe Roman Forum). Time, carelessness and a number of sacks suffered by the city did the rest. In Berneri's days, the Forum looked like a large 'hole' in the middle of a largely rebuilt and urbanized Rome, an open field scattered with ruins of all sizes, some of which sticking out of the muddy ground, having been buried over the centuries by a considerable rise of the street level.

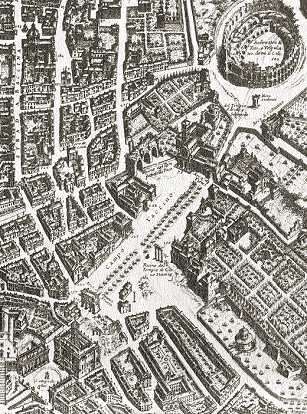

The area had meanwhile been adorned by a double row of trees, that formed a path running from the church of Santa Francesca Romana to the arch of Septimius Severus (still half sunken in the ground), as described by Berneri's verses; this is perfectly consistent with the view in Giovanni Battista Falda's map of Rome (1676). |

Campo Vaccino, in G.B. Falda's map;

note the double row of trees |

Campo Vaccino, in an engraving by G.B.Piranesi |

Despite the popes' interest for antiquity had already been awakened since the Renaissance, and despite some considerable finds had already been made in this area (such as the famous reclining statue known as Marforio), a real excavation campaign did not take place before the second half of the 19th century, very gradually at first, then systematically, when the Papal State fell (1870) and Rome became the capital of the Kingdom of Italy.

Unfortunately, what archaeologists found, and what we still see today, are mostly ruins. |

CAPITOLIUM HILL

the tournament organized and won by Meo (Canto XI)

The history and evolution of Capitolium Hill is fully dealt with in the Miscellaneous section, which also provides a wider selection of images.

Already during the Iron Age (10th century BC), the top of the hill was the site of one of the early settlements that in time developed into a city. By its base ran a stretch of the Servian Walls (c.340 BC), now no longer standing, along which the gate called Porta Fontinalis was found, on a site now belonging to piazza Venezia.

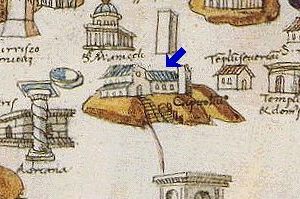

the Senators Palace on the Capitolium (arrow),

detail from the map by Pietro del Massaio, 1472 |

On the uppermost peak of the hill stood the Temple of Capitoline Jupiter, the largest and most worshipped among Rome's temples, with two more, namely the Temples of Admonishing Juno and of Minerva at slightly lower levels. The main temple overlooked the Forum from above, and from the same Forum the temple could be reached by following a no longer extant pathway, that climbed along the southern side of the hill. Today the main approach to the top of the hill is on the opposite side, which in the days of ancient Rome pointed towards the Campus Martius field and looked like a bare, steep slope.

During the first half of the Middle Ages, Capitolium Hill fell into a state of abandonment, where sheep grazed (whence its alternative name monte Caprino, "sheep hill"), up to the 12th century. |

Then, over the remains of the ancient Tabularium (state archive), the large Senators' Palace was built; here Rome's administrators (the Senators) held their meetings, and the site gained again its social importance.

But besides the palace, the hill was still a rough slope with a bare open space at the top; pedlars kept selling food here during a sort of fair, periodically held, whence the hill was nicknamed faba tosta (i.e. "roasted broad bean").

Pope Paul III (1534-49) had the idea of finally arranging the space above the Capitolium, and commissioned this work to Michelangelo. The famous architect enlarged the preexisting Senators Palace, and drew twin buildings on both sides of the square, namely Palazzo dei Conservatori (right side) and Palazzo Nuovo (left side). The works took a long time; Michelangelo died in 1564, before they were finished; two of the buildings were completed by Giacomo Della Porta and Girolamo Rainaldi (c.1605), while the making of Palazzo Nuovo only took place during the first half of the 1600s. |

Capitolium Square, detail from Giovanni Battista Falda's map (1667) |

So, ever since, this was the final arrangement of the famous square, mentioned by Berneri: three large buildings, whose lightings shine from the sides of the square up to its bottom (Senators Palace) and, in the centre, the famous statue of

Marcus Aurelius. The later once stood in the Lateran grounds, and was moved here in 1538. Michelangelo drew for it a high base, the one over which Nuccia climbs - taking the risk of breaking her neck - to watch Meo's feats.

VIA DEL CORSO

the celebrations organized by Meo (Canto VII)

|

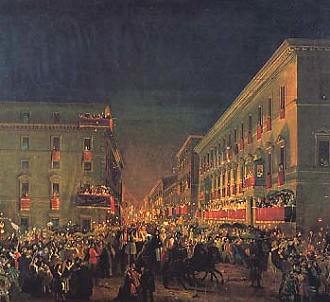

The pageant described in Berneri's poem, held for extraordinary reasons, is quite similar to the standard celebrations

held once a year during the Carnival days, along via del Corso and the surrounding streets (see the Curious and Unusual section).

The lightings were a constant element of this important Roman eight-day festival, which ended with a special event known as the candle race. The paintings that depict this race, such as the one by Ippolito Caffi shown on the left, suggest the atmosphere and the colours that Rome's streets may have had during public celebrations, such as the one organized by Meo.

← The Candle Race along via del Corso (detail), by Ippolito Caffi, c.1850 |

PIAZZA NAVONA

Meo's complaint against the slanderers (Canto III),

Meo's street performance of the siege of Buda (Canto XII)

This long and oval plaza, credited by many as the most beautiful square in Rome, is also described in The Rioni section (see Parione district), and in Legendary Rome. For the history of its three fountains, instead, the relevant monograph is a better source of information.

Piazza Navona maintained the shape of the arena of emperor Domitian's stadium, which since the late 1st century AD stood on the same site of the square. Its name sprang from the athetic games it hosted (agones in Latin).

During the Middle Ages, this site was in fact known as Platea Agonalis, or Campo in Agone; such names were still in use in the 17th century, although in the common language it was already called piazza Navona. This word is a corruption of the original Agone, which changed into Navone ("large ship", maybe due to the shape of the place), and then turned into Navona.

the Pamphilj coat of arms, on both sides of the fountain

(move the cursor over the picture for the verses) |

the lion coming out of the den

(move the cursor over the picture for the relevant verses)

When Berneri wrote Meo Patacca, the final arrangement of piazza Navona had been completed only about forty years earlier; its central fountain, in particular, still kept fascinating Romans and foreigners alike, due to its innovative concept and awesome look. |

Therefore, we should not be surprised that Berneri dedicated twenty-one octaves (over one quarter of of Canto III!) to describe the square, fourteen of which dedicated to the Fountain of the Rivers alone. Curiously, not a word was spent for the church of St.Agnes, built in the same years. This clearly shows how while Bernini's works were particularly successful among all social classes, Borromini, yet being a very talented architect, was indeed kept in less consideration than his rival.

| Berneri left a very brilliant description in verse of the many details of the Fountain of the Rivers (a few examples are shown in this page), including the 'crocodile', which is actually an armadillo. In the past centuries, fountains, but also statues, paintings and any other form of figurative art, were looked at by the common people as a sort of virtual reality; although the large majority of them were illiterate, they almost had an innate sense of aesthetics, and were able to tell at first glance good art from bad art, their abrupt judgement having a strong impact on artists' carreers, according to whether their works were welcomed with positive comments or sneered at. |

the fish that swallows the water

(move the cursor over the picture for the verses) |

piazza Navona in G.B. Nolli's map (1748);

a circle marks the site of the mock siege,

and a dot indicates Pasquino's corner |

The mock siege of Buda performed by Meo is set on a spot just outside piazza Navona. The description provided by Berneri is once again so precise (Slightly further, there is a space / Where vicolo della Cuccagna ends) that its location can be easily identified. Today the place has more or less the same look it had in those days. |

the place at the end of vicolo della Cuccagna (the alley on the left):

the spot is still basically the same as it was in the late 1600s |

THE 'GIRANDOLA' AT CASTEL SANT'ANGELO

the fireworks display from the Castle (Canto VIII)

The Girandola was a lavish firework show, a very popular Roman tradition held from the late 1400s until 1886, when it was discontinued because of the damages caused by vibrations and by the explosions to the wall paintings of the castle.

the girandola at Castel Sant'Angelo,

by Jakob Philipp Hackert (1775) |

In 2008 it was retrieved (with the due care), and is now scheduled on June 29, the day on which Rome's saint patrons, St.Peter and St.Paul, are celebrated.

The old event consisted of a display of several kinds of fireworks, from the simple mortaletti, described in detail by Berneri, to the more complicated ones, that burst into streams of coloured lights. The origin of the celebration apparently dates back to the 16th century; it is said that it was devised by Michelangelo.

It was held on particular celebrations; the choice of Sant'Angelo Castle as a location allowed the show to be enjoyed by a huge crowd. The present girandola only takes place once a year.

The coloured lights that rose from the Castle into the dark sky, reflecting in the Tiber's water, left the spectators in awe, as they still do today. |

the girandola on June 29, 2014 →

Several authors left a description of the Girandola, either in verses or as drawings, paintings and engravings; among the latter are Hendrick van Cleef (first half of the 1500s), Jakob Philipp Hackert, Francesco Piranesi, Francesco Panini and Joseph Wright (1700s); Franz Theodor Aerni and Ippolito Caffi (1800s).

The most crucial moment of the display, as mentioned in Canto VIII, at the end of the show, was the actual girandola, i.e. the simultaneous firing of a great number of flares, a technique that is said to have been improved by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and whose glow ignited Rome's sky as during daylight, although the show was quite ephemeral: |

|

|

Son cose belle sì, ma a parlà schietto,

Il finir troppo presto è il lor difetto.

|

|

They are indeed nice things but, to be frank,

Their only weak point is to last so little. |

THE JEWISH GHETTO

the siege of the ghetto (Canto XII)

The ghetto, or 'the enclosure of the Jews', as it was called in the days of Paul IV, who in 1555 had established it by decree, is fully dealt with in Curious and Unusual, where details and pictures can be found.

In Meo Patacca we read that the ghetto's gates were five all together; having the district become heavily overcrowded, with several thousands living there, only in the first half of the 1800s the boundary of the enclosure was slightly enlarged and a sixth gate was opened.

More than the place itself, for which Berneri spends but a few words (It's a rather miserable enclosure of streets, / As it is shady, and rather saddening.), the author mentions the Roman Jews' language.

|

one of the ghetto's corners (watercolour by Ettore Roesler Franz, c.1885) |

piazza Giudia, outside the Ghetto, whose main gate is featured

on the right; the pole on the left was used for punishing offenders |

The Jewish-Roman dialect, rich in words and expressions borrowed from Hebrew (and corrupted), represented a somewhat parallel dialect to Rome's standard one, spoken indeed by much fewer people, but with the same linguistic importance. Unfortunately, it is no longer heard in the streets, but an important heritage was left by poet Crescenzo Del Monte (1868-1935) with his collection of sonnets, and even translations into Jewish-Roman of excerpts of works originally written in Roman dialect and Italian.

|

Let us conclude with a curious detail.

At the beginning of the story, Berneri mentions cafes and public houses where the people used to meet; one of them was called 'The Three Kings'.

via dell'Arco di S.Marco

(E. Roesler Franz) |

We cannot exclude that this may have been a fantasy name, as in those days many hotels and inns were called "The Three Kings", not only in Rome but in other cities too.

Among the famous series of watercolour paintings by Ettore Roesler Franz (1852-1907), known as Vanished Rome, one of them features via dell'Arco di San Marco, a no longer exitant street once located by the present piazza Venezia. On the right side of the painting, a small notice features the ALBERGO DEI TRE RE ("The Three Kings hotel"); it is intrigueing to think that this may have been the same establishment mentioned by Berneri in his poem.

Peaceful stood Rome

During year sixteen thousand eighty-three. |

|

|

|

The same place is also mentioned by Giuseppe Gioachino Belli in a sonnet dated September 13, 1830, in which a commoner, chased at night-time by a Swiss papal guard, rushes along this street:

E con la patta in mano pijo l'Arco

De li tre Re, strillanno: « Vienghi puro ».

(La pisciata pericolosa, vv. 8-9) |

|

And holding the flap of my trowsers

I flew past the Three Kings Arch, shouting: « Come and get me ».

|

|